The Mendsmith Project: Nick Dong

As the Encyclopedia Britannica notes dryly in its entry on decorative art, the distinction established between media such as ceramics, glassware, textiles and jewelry and the more elevated fine arts (principally sculpture and painting) is largely a modern one. Such a hierarchy-- based on the notion that the decorative arts comprise useful objects and fine art, that which is purely aesthetic-- seems arbitrary. In the context of contemporary practice, ‘functional’ has taken on a whole new set of meanings. Nick Dong’s Mendsmith project exemplifies this conceptual complexity. Through a combination of social practice and extraordinary craftsmanship, Dong focuses on a kind of emotional, psychological and spiritual repair.

The road to realizing his mending venture has taken a complicated series of twists and turns. A degree in painting and mixed media in college was followed by military service in his native Taiwan. Dong then attended graduate school at the University of Oregon in Eugene, where he started working with metals. He described his first encounter with this new material to me as “falling in love.” Drawn to the full spectrum of new possibilities that metal offered, he made both large installations and functional personal objects, experimenting widely.

He finished his degree in 2002, taking a job in San Francisco as a bench jeweler[1] at a high-end store. His work often involved making wedding rings. Even when tasked with this relatively straightforward commission—one that usually focuses on what stones and metals clients prefer, using a design from a set repertoire-- Dong spent time talking with the prospective couples about themselves, transforming their stories into physical elements that he incorporated into the rings he made for them.

In 2005, when a close friend lost her husband, Dong knew that he wanted to do something for her that was more meaningful and lasting than simply offering his condolences. With her permission, he set out to transform the couple’s wedding rings into something she could treasure as a representation of the love they had shared. Discovering that his friend’s ring fit inside her late husband’s, he cut the smaller band and turned it inside out.

Now, the engraved messages of love that were originally inside each ring were face to face. Attaching the bands together in what he has described as ‘an eternal embrace,’ he made his first mend.

Throughout that first decade after grad school, Dong did performative work and ambitious installations. For a number of years, he went back and forth between the US and Taiwan every six months, working on his permanent residency status. He exhibited pieces in group and solo shows from Norway to Oakland— including a 2007 show of four artists doing experimental work in metals that took place at the Massachusetts College of Arts and Design. Indirectly (a student who saw that show later became a curatorial intern), this led to an invitation to participate in ‘40 under 40’ at the Renwick Gallery in Washington DC. This important 2012 exhibition featuring forty artist born since 1972 commemorated the 40th anniversary of the Renwick’s establishment as the Smithsonian museum featuring contemporary craft and decorative arts.

In 2013, Dong decided to focus on his fine art practice, founding StudioDONG, which he describes as “a creative enterprise devoted to the design and manufacture of products that ignite experiential moments.” He was also teaching workshops internationally and guiding metals majors at California College of the Arts through their senior projects. There were some interesting and high-powered consultant jobs. Then, in 2015, he was invited to a participate in an exhibition /residency at the Center for Creativity and Design--a nonprofit in Asheville, NC that is dedicated to moving craft forward through research, exhibitions and supporting the next generation of makers and scholars.

As he considered what he should do with this opportunity, Dong’s thoughts returned to the united rings he had made for his bereaved friend ten years before. What if he were to make similarly meaningful pieces for others who had suffered the loss of a loved one? In that moment, the Mendsmith Project was born. “The word itself is a play on metalsmith,” he told me. “As artists, we have our technical skill set and our creativity-- the ability to transform something, from ugly to beautiful, sad to radiant. We can actually take on the task of not just making the world more beautiful but also to transform people, to help others.”

Dong decided he would ask each participant to bring two small objects or pieces of jewelry of personal significance: one belonging to the loved one, the other to the participant. He then sat down with each of them, encouraging them to talk about the loss they wanted to address. Over the course of ten days, he was able to complete seven pieces, working in the gallery where visitors could watch him. Most were curious what he was doing, so he would stop for a moment and tell them about what he was working on, and why. “I was performing, in a way—sharing true stories… about my efforts to help others deal with grief. I wanted to show them that art can be something that can directly address their wellbeing, their feelings, their loss-- and not just be something pretty to hang on the wall.”

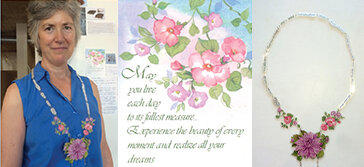

There were some surprises. The things people chose to bring were not always made of precious materials—like the birthday cards that Anita had received from her beloved grandmother Lena. Dong made a necklace from the card’s pictorial elements and text. A pair of tiny pearl earrings hangs from the central flower.

Another participant, Stephanie, had not ‘lost’ her husband: not to death, that is. He had survived a prolonged battle with brain cancer, diagnosed only eighteen months after they had married, but had been transformed by the experience from the brash, romantic man who had courted her into a different person.

During that courtship, Bill had presented Stephanie with three (!!) engagement rings, each with a larger diamond than the last. She brought these to Dong, supplemented with a cubic zirconia necklace Bill had also given her.

Dong joined all four stones in a single, bold setting that evokes a golden crown. In a way, it represents not only the couple’s marriage but their family, which now includes two children.

Kato, a cheerful woman in her seventies, wanted to commemorate her beloved poodle Diego-- her faithful companion through her own painful treatment and recovery from cancer. Not long after she was given a clean bill of health, Diego became sick with the same disease, dying quickly. As Dong noted, “Kato believed that he had traded his life for hers.”

Dong took a necklace that the dog had destroyed in his rambunctious youth, creating curling, delicate bits of oxidized silver and assembling them into what looks like a ball of poodle hair. He suspended it from a red ribbon—echoing the scarlet collar that Diego once wore.

Ruth brought Dong a Scottish brooch her father had given her that honored their shared heritage. She had loved him and seemed to have spent much of her life feeling that she didn’t measure up to his expectations--but in the end, realized that he not only loved her but was proud of her accomplishments. Her mother had passed away and her father had remarried, so she also brought his two wedding rings.

Dong transformed the rings into a new brooch, similar in shape but decorated only with two simple gold beads, symbolizing how both her father’s nurturing and his example had helped her to become who she is. You can see Ruth and her father at the beginning of this essay.

_______________________________

After returning home, Dong tried to figure out the best way to continue mending. He thought about all the people who were sustaining unimaginable losses from natural disasters, or the mass migrations caused by war. He applied for grants to continue his project in different locations. It has been difficult, however, to persuade funders that such a labor-intensive, one-on-one process will yield significant enough results to merit financial support. Besides, he admitted to me, the grants he has applied for “were more about pushing jewelry to the next level – getting it to be regarded more as fine art.”

In the end, he decided to create his own opportunity. This summer, he took up residence for a month at Mercury20 Gallery in Oakland. Members of the public were once again invited to make appointments for a consultation. As with the Mendsmith Project in Asheville, they were asked to bring in small objects or pieces of jewelry, something of their own and something belonging to the loved one with whom repair of some kind was desired. Dong worked in the gallery during the month, bringing in a workbench and tools.

Six people signed up. I was one of them. (In the interests of research, I thought that this was the best way to learn about what he was doing.) All of the participants, as it turned out, were women; the same had been true in Asheville. “Maybe men can’t deal with grief the same way that women do— it’s a taboo subject. They aren’t supposed to be vulnerable,” Dong told me. He was silent for a minute. “Or maybe men aren’t as ready to share their stories with a random stranger.”

This time, two of the pieces he made were in memory of lost partners: Audrey, for her late husband Michael, and Megan, for her wife Angela. Four-- including my own—addressed the repair of relationships with long-gone parents or grandparents.

Audrey brought four gold rings: their wedding bands, an engagement ring consisting of a single large pearl surrounded with rubies in an elaborate setting, and a twelve-year anniversary band punctuated with tiny diamonds. She talked about Michael, mentioning that he would bring her roses every week. When Dong thought about how to represent the life that the two had shared, he decided to transform the wedding bands into a tiny gold rose with the pearl and gems at its center, hanging from the anniversary band. The necklace unites the rings, commemorating the affectionate ritual of flowers the couple had both taken so much pleasure in.

To celebrate her relationship with her beloved grandmother, Maya brought four silver rings and the central part of a fifth-- a large oval of agate stone. Dong decided to combine elements of three of them. He used the metal from a wide silver band to make a mount for the agate and reconfigured a cluster of colorful gems, creating an unconventional two-sided ring. It looks beautiful on Maya’s hand.

And me? I told Dong that repair wasn’t something I’d really thought about, for my relationships with parents gone now for a decade or more. I still miss my mother: there are so many aspects of parenting she could have weighed in on, and so many other questions I still have about her but never got around to asking. My father—more distant in life as well as death—was harder to parse. To represent him, I brought a little silver pin of a bell from Innsbruck: not exactly something he had owned, but a souvenir from his native Austria that he’d given me as a child on the only trip we’d taken there as a family. A heavy silver ring my mom had worn instead of her massive engagement diamond in her last years stood in for my relationship with her, with a button from a coat she had loved. Finally, I added another silver pin of two battling dragons. Perhaps that was their sometimes-contentious relationship. I wasn’t sure, and couldn’t remember exactly where it had come from, or when—just that it seemed to belong with the other things.

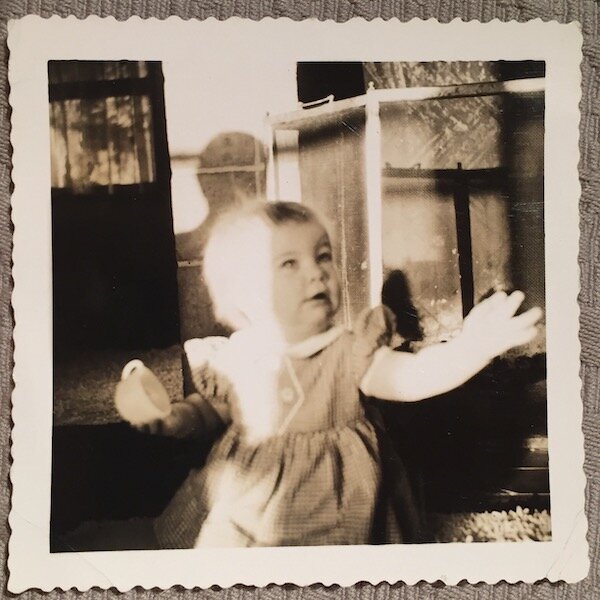

Dong confessed that it had taken him a long time to figure out what to make for me. Under his questioning, I’d told him quite a lot about my parents. Their awful families of origin; how they had met during the war and suffered through a series of tragedies, including the death of their first child—but had simply continued on, largely on emotional autopilot. He asked me for a picture of me with them. Oddly, the only one I could find was a haunting snapshot of me at two, my mother’s shadow falling across the scene.

Finally, Dong decided that something like a medal (for bravery? Endurance? Amnesia?) would be right. He removed the flower from the tiny bell and placed it on the button, which he then framed with two graceful curves cut from the ring. These somehow suggest the handles of a trophy, or—maybe— two halves of a heart. Hanging below, inside of a three-lobed circular frame, is a single dragon. It seems to be looking at its reflection in the mirror-polished silver. Perhaps the dragon is me, still supported by my long-gone parents—from a distance, as in life. The three-part frame around it suggests that the three of us remain joined, in the mysterious way that parents remain connected to their children even after death.

I asked Dong about everyone’s response to their ‘mended’ objects. He shrugged, and smiled. “What came out of this project depended on what went in… but people were surprised at how significant the experience was of seeing the transformed objects.” Bending forward, he drew my attention to one last detail in mine. The link that connects the two parts, he showed me, is a tiny nail, bent into a circle. “It was the ringer inside the bell,” he said. And with that, the mend was complete. When I look at it, I’m reminded that what I learned from my parents will always be the foundation of what I am now. We are formed by the past, but— if we are lucky— we can make our own present.