Mending 3: Jim Melchert

I.

I like words that start with re: rethink, revisit, reassess, reenter. I think that’s how our minds work—we keep circling the same issues, but with increasing clarity and depth. -Jim Melchert

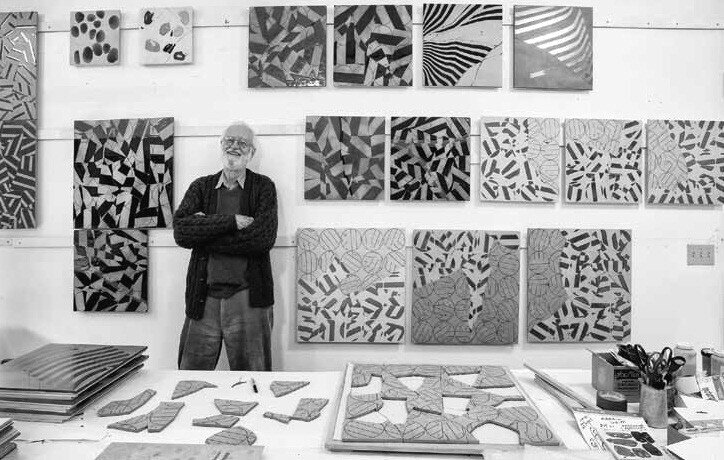

Jim Melchert’s work of the past thirty years can be described, at once accurately and poetically, as a transcendent exploration of mending. Using commercially-manufactured floor tile as his primary material, Melchert engages in deliberate breakage and consequent, system-based repair and elaboration.

Still, these words hardly seem to do justice to the elegant permutations and combinations of color and line that spread across Melchert’s compositions of reassembled shards. In pieces that range in size from a single twelve-inch square to dozens of them combined together in a vast mural, he systematically follows lines of fracture with planned actions. These include, but are not limited to, painting lines of glaze—single marks or repeated bands that echo across the reassembled surface; marking the surface with dots that map sharp bumps or hidden corners along the tiles’ edges, invisible to observers; drawing or painting circles that form a grid, or are scattered across a surface like a handful of tossed marbles, and linear gestures that echo the broken shapes themselves. In a recent series titled Vertices for Dancing, for example, small bicolored orbs spill across the spidery cracks, seemingly engaged in some complicated fandango.

Most of these pre-ordained actions take place in relation to the pointed end of the largest broken pieces. This is the spot where, as Melchert explains, the energy moving through the fired clay has found the weakest link, breaking the chained molecules-- much as soil and rocks separate along a fault line in an earthquake. Factory-made tiles may seem identical and uniform, but on a microscopic level they are as unique as snowflakes. Clay consists of a mass of tiny plates, their bonds stronger in some places than in others. Once fired, it breaks according to the specific distribution of these strengths and weaknesses.

Though conceptually-based work has been around since Marcel Duchamp made a urinal into art in 1917, the birth of Conceptualism as a movement dates to the late 1960s, when Sol Lewitt[1] began exploring the idea of making art from a set of directions. Unlike Lewitt’s pre-defined actions, though, Melchert’s execution remains unpredictable. Breaking something can be manipulated, but not controlled.

Onto concrete walkways around his house and studio, he drops a porcelain tile measuring a foot or more in each dimension. Endless experimentation has taught him what spots are the most conducive to the kind of destruction he desires: at what angles the tile should be released, from what height.

This moment is usually perceived as the end of the life of a ceramic object, rather than its beginning. (Melchert is amused by the fact that “once you break a tile, no one is going to give you two cents for it—but after you work on it, they’ll pay a lot for it. Art is so much about transformation—straw into gold. Clay is just mud, but artists make something from it.”) Shattering, he explains, has become the opening gambit for a Zen-like interaction. “The gift the clay gives you as a partner is when you discover the interior structure. But it’s like someone who has just made a first move in checkers—it’s like a challenge, and then you move, then other person makes a move. Whatever I do, the tile comes back with a response.”

II.

People solve problems in many ways. Once I gave my studio assistant a tile I had broken and asked if she could repair it with masking tape but with as little tape as possible. She mended it in a few seconds and differently from how I would have done it. Afterwards I gave the same problem to various friends when they dropped by. I glazed the repaired tiles except where there was masking tape.-JM, Repair Series, 2003

Melchert’s absorption of the ideas that have driven avant-garde art for the past sixty years began during his first stint in graduate school. By the time he enrolled at the University of Chicago’s MFA program to study painting in 1955, he’d gotten a BA in art history at Princeton and spent four years in post-war Japan teaching English. Posted to Sendai --a northern city where the US believed there was industry, and thus bombed most of it flat—he remembers walking through vast empty areas where houses had once stood. He met other young Americans; most were sent there by church groups- the American Friends were particularly active—including Mary Ann Hostetler, a Mennonite preparing for missionary work who would become his wife.

The curriculum at the U of C was still somewhat traditional, including not even a whisper of Abstract Expressionism. Outside of school, however, Melchert met interesting figures in the city’s art world who introduced him to new ideas. His own paintings remained steadfastly representational; for his thesis show, he produced a triptych of still lives that “owed a lot to German Expressionism.[2]”

Once he’d completed his MFA, he took a teaching position at a small college in Illinois so he could continue to paint. As the only art faculty, he was asked to lead a ceramics class. Over the course of the semester, he became increasingly interested in the possibilities that clay offered. So it was that the following summer he spent some weeks in Missoula, Montana, taking a workshop with one of the medium’s most notorious young rebels, Pete Voulkos.

The experience was transformational. Voulkos showed students slides of works by painters such as Rothko, Kline and de Kooning, as well as ceramics by Miro and Picasso. Melchert was so inspired by both class and teacher that he decided that he would pursue a second master’s degree. With his wife and three young children, he pulled up stakes, and they moved to Berkeley in 1959. Voulkos had just begun to teach there, at the University of California.

[It is hard for me to imagine now what it must have been like to arrive in the Bay Area at the end of the fifties. My own family had just moved away, my parents having finished their graduate degrees at UC Berkeley, courtesy of the GI Bill. In later years, my mother often alluded to the way it was getting crazy when they left—poets! Beatniks!—though she found some things Californian, like artichokes and avocados, to be delicious.]

Despite their years in Japan, for a young couple from the Midwest like the Melcherts, their new home must have seemed like an exotic adventure. On Sundays, they would take out a map and place a dot on a random spot and then just put the kids in the car and drive there to see what it looked like[3]. In time, of course, the strange became familiar. Melchert still lives and works in the hundred-year-old house in the Oakland hills where he and his family moved in 1964.

In 1961, having completed his MFA in ceramics, he returned to teaching: first at the San Francisco Art Institute, and then at UC Berkeley. In his own studio, he felt he had a lot of catching up to do, having attended a liberal arts college rather than art school. He was working with clay, but, intensely curious about breaking-edge practices like performance and conceptualism, he began to experiment.

In 1972, he created the first iteration of Changes—a near-legendary performance piece still talked and written about today. One by one, he and nine other participants immersed their heads in a basin of ceramic slip (the liquid form of clay), then sat in a line on a bench as the goop dried, the clay shell turning their bodies into vessels. As Melchert later wrote, “It encases your head so that the sounds you hear are interior: your breathing, your heartbeat, your nervous system. It is surprising how vast we are inside.[4]”

Three years later, his solo show at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art consisted of slide projections. He also made a series of ‘graphite rubbings’-- soft outlines of a square or rectangle on sheets of paper or envelopes, indicating the hidden presence of a photograph. The picture would be described in the work’s title, but remained unseen. You had to simultaneously imagine it-- and take it on faith that it actually existed[5].

An even bigger change in his life as an artist was coming. In 1977, Melchert was tapped for the challenging job of directing the Visual Arts Program at the National Endowment for the Arts in Washington. The job was enormous and absorbed all of his time. Towards the end of four and a half grueling years, he was invited to a conference in Italy. When he stopped off in Cairo to visit his son, he remembers seeing a great deal of architectural tile work—something that has been developed to an extraordinarily high level of refinement in that part of the world. “The walls weren’t these big solid things containing space. The walls were the skin of space.[6]”

It occurred to him that working with and on ceramic tile might yield some interesting results. It was also a way to repair his fractured relationship with clay.

He began experimenting with pattern, but found its tyranny stifling. “You begin at one side,” he has recalled, “and you must carry it out over a whole field.” Then, in 1984, he was appointed to serve as the head of the American Academy in Rome. During his tenure there, both his time for art making and his access to ceramic facilities were limited, so he focused on making large drawings. He resumed working with tile again after his return to Berkeley in 1988, and since his retirement from teaching, he has been in the studio full time.

III.

There is a crack in everything, that’s how the light gets in.—Leonard Cohen

When looking at Melchert’s broken and reassembled pieces, it can be fruitful to try to focus on the way each seemingly-random network of cracks follows that hidden molecular path: the line of least resistance. The act of breaking alters the perfection of the square, reducing it to a group of fragments. Glaze is then selectively painted on the surface of all or some of these sharp-edged pieces, which are (re)fired in a kiln. When all of the parts are reassembled to make a square once more, the stripes or dots or circles of glaze draw attention to the randomness of the cracks, even as they make the breakage into something harmonious.

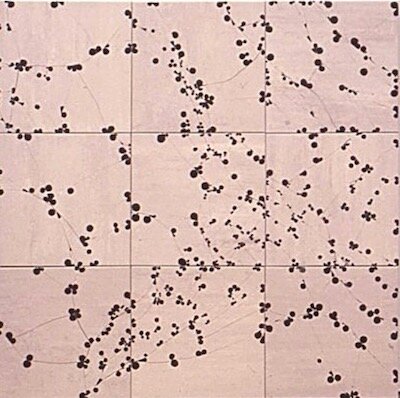

In Ecco (1994), an early tile experiment, two horizontal red chalk lines seemingly hold together a shattered Mexican paver. Its simplicity belies the trial and error that must have preceded its elegant gesture. By the early 2000s, works in the Yield series combined several tiles-- four or nine—in a group, their surfaces punctuated with dots of black or red. These are the works in which the mark’s location was determined by sharp bumps detected by the artist’s fingers, hidden from viewer’s eyes.

“I liked seeing what resulted when the shards were reassembled,” Melchert wrote about these pieces. “The field of dots reminded me of both constellations above, and land seen below from an airplane at night with its many scattered lights from settlements.[7]”

The word yield is both active and passive, noun and verb, and can mean both producing and giving up, or possibly both at the same time. Melchert’s multi-tile compositions from this time similarly evoke a mischievously diverse range of antecedents, ranging from Carl Andre’s floor pieces to Robert Irwin’s early dot paintings, or even Duchamp’s Three Standard Stoppages (1913-14). When I look at them now—I first wrote about them in 2002—they make me think of delicate ink paintings of cherry blossoms, or winter berries on slender branches.

In the Repair series (2003), Melchert experimented with a different approach. Asking others to ‘fix’ a broken tile using the fewest pieces of tape possible, he then glazed all but the taped-over areas. In a way, these are the opposite of the Yield works, in which the dots record imperfections that, through touch, only he was privy to. There is something charmingly obvious about the Repairs, but also anomalous: they require participation by others.

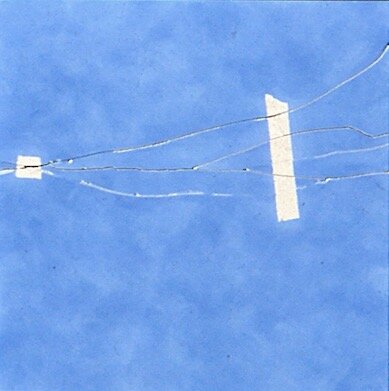

The Eye Sites series of 2006-8 focuses on drawing our attention to the flow of energy through the breaking tile. A thick diagonal line of either graphite or glaze leads from the acute, knife-sharp points of selected shards into those fragments’ broadest expanses. Again, the punning title offers multiple readings. Perhaps the line’s function is to lead the viewer to a visual resting place (a site for sore eyes?). Each line also looks like the letter I. The edges of the graphite marks have a delicate, ghostlike softness, as if they have been physically worked into the tile’s surface.

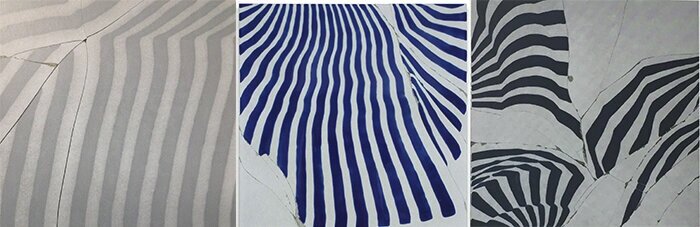

Sometimes, the marks Melchert chooses to make are dictated by the shape of a fragment’s longest edge. Tracing it, he makes a cardboard template, used to lay out each succeeding painted line. In To RE-Descend (2007), the lines parallel each other, like the marks created in raked gravel found in Japanese gardens. In other pieces, he fans the lines as they advance across a fragment’s surface. In 26 Minutes (2008), this process results in the delicate illusion of multiple vanishing points, or some mysterious system of topographical rendering. The lines in Eighteen Seconds (2008) ripple and curve until they suggest ribbed three dimensional forms.

In the beginning, every fragment of tile was striped. Later, Melchert chose to leave a number of pieces blank. He describes the work that resulted as “less rattled, or agitated.” In addition, the empty fragments create another level of visual counterpoint.

One group of works from around 2011, called Misfits, followed a complicated plan. One by one, he would pick up the larger shards of a broken tile. Cradling each in one hand, he’d pour a little pool of glaze on it and shift it around, creating an irregular blob. When he thought the shape looked interesting, he’d stop and let it sit for a moment. “Then I’d run it under the faucet- and only the rim of the shape, where the glaze had dried around its edge, would remain, “ he told me. “That’s what you see in the images-- these shapes, a bit like potatoes.” To my eye, they resemble cells, as seen under my high school microscope. Whatever they are, each is as unique as the fragments they decorate. After firing them, Melchert carefully drew a grid of circles—a gesture that both anchors the irregular shapes and accentuates their eccentricity.

This counterpoint between freeform blobs and carefully-limned circles suggests music, which is not surprising. Other bodies of work— Scores and Performances (2013) and Piano Scores (2014) -- refer directly to notation and composition. In the first of these, grids of drawn circles interact with painted color and form, in increasingly complicated ways. The drawn circles, Melchert told me, are the scores; the painted ones, in vivid blue, red or orange, are the performances. Piano Scores reflects his love for jazz— Duke Ellington, in particular— but also suggests the dynamic relationship between black and white keys.

Chance was an important element in the creation of these works; he would spin a plastic ruler on each fragment and draw its two parallel edges where it stopped moving. Melchert used the same spinning-ruler system to create Riven/ River (2014), his public art piece at San Francisco Airport, a six by fourteen foot tour de force.

When the Cat in Copy-cat was a dog (2016) takes the shape of a simple break and replicates it, like an echo or a shadow. A suite of pieces from this series, now in the collection of the Gardiner Museum in Toronto, includes the photograph that seemingly gives the series its name. It shows his granddaughter and the family dog, lying on his dining room floor next to each other in the same crossed-leg repose. This charming, funny picture seems to reach back far into Melchert’s artistic past, touching on his experiments with performance, projected images, and even the envelope rubbings. At the same time, it reveals his openness to the moment: a willingness to accept what comes his way by chance and allow it to lead him towards something new.

IV.

In the beginner's mind there are many possibilities, in the expert's mind there are few. -Shunryu Suzuki

The arc of an artist’s career is usually described in such a way that the more mundane parts, such as employment (since most artists today do have other work besides their studio practice) remain magically invisible. In Melchert’s case, these other activities are inextricably interwoven with the objects and ideas he has produced over the past five decades. His commitment to a larger community through leadership and teaching never altered his intense interest in making art. Still, the meandering path he has taken (Washington, Rome, academia) has led to his work being less widely known than that of many of his peers—particularly considering the level of international recognition and exposure that his early work received: inclusion in numerous important exhibitions at places like the Whitney Museum of American Art, Documenta, and Biennials in Sydney and Sao Paulo, as well as numerous solo shows. Alluding to this once, he remarked that his re-entry in the Bay Area art world after his directorship at the American Academy wasn’t without its difficulties, saying wryly, “When you get off the bus and you get back on later, you find that you don’t always have a seat.[8]”

Looking back at nearly ninety, Melchert has described the four years he spent in Japan in his early twenties as the most influential experience of his life. Being able to live outside of his own culture and experience another as it repaired itself helped to form his sense of perspective and judgment. Not unlike the invisible structure of molecules inside a tile, it shaped his direction.

I asked him once if he thought that art could heal society. He thought for a moment, and then started talking about the Great Depression—a time when mending was urgent. There were magazines in the early ‘30s, he told me, that taught people how to make things for themselves, which was both comforting and empowering.

“And there’s singing,” he continued. “In churches, everyone singing together gives people a true feeling of unity. Or in Zen practice, the chanting… these are all mediums for mending and healing.”

The excitement and enthusiasm with which he still approaches making work invokes the great Zen teacher Shunru Suzuki’s ‘Beginner’s Mind’-- a place where there are always fresh possibilities for someone who remains open to them. Melchert’s most recent pieces are made from black tiles, onto which he applies irregular shapes of white glaze punctuated with tiny circles in primary colors. The conversation between black and white is mysterious and lively, as one or the other alternately recedes or pushes forward, their stacked forms following the long curving cracks. They bring to mind birds, or paper caught by a breeze. Thinking back to what has come before them, I believe that I can see how they came about. At the same time, they seem like something altogether new.

From the age of 6 I had a mania for drawing the shapes of things. When I was 50 I had published a universe of designs… At 75 I'll have learned something of the pattern of nature, of animals, of plants, of trees, birds, fish and insects. When I am 80 you will see real progress. At 90 I shall have cut my way deeply into the mystery of life itself… I am writing this in my old age. I used to call myself Hokusai, but today I sign myself 'The Old Man Mad About Drawing.’-Hokusai Katsushika

_________________________________

[1] “When an artist uses a conceptual form of art, it means that all the planning and decisions are made beforehand and the execution is a perfunctory affair. The idea becomes the machine that makes the art.” Sol LeWitt, “Paragraphs on Conceptual Art,” 1967

[2] Oral history interview with James Melchert, 2002 September 18-October 19, by Renny Pritikin, Smithsonian Archives of American Art

[3] “A conversation with Jim Melchert: Lucky breaks,” Richard Whitaker, in Works & Conversations, 12/1/2007 http://www.conversations.org/story.php?sid=129

[4] Harrod, “Out Of The Studio, Or, Do We Make Better Work In Unusual Conditions?”,Dorothy Wilson Perkins Lecture, Alfred University, 11/5/2009 https://ceramicsmuseum.alfred.edu/perkins_lect_series/harrod/

[5] I remember encountering a group of these pieces at the Art Center in Madison, Wisconsin in 1977, and being enchanted by both the idea and the execution: the small, neat writing below soft gray rectangles and squares. I didn’t realize these were Melchert’s pieces (having long since forgotten the artist’s name) until many years after I had met him and begun to write about his work.

[6] Conversation with John Held Jr., 2016, quoted in “Palpable Space: Jim Melchert’s ceramics,” SFAQ, June 21 2016

[7] Artist’s website

[8] Oral history interview with James Melchert, 2002 September 18-October 19, by Rennie Pritikin, Smithsonian Archives of American Art