Mend

My mother was not much of a Mender. Like many of the women in her generation—required to leave the workforce after WW2, to make jobs available for returning GIs -- her relationship with domesticity was somewhat fraught. She liked to cook, but found most of the rest of her wifely duties to be mildly ludicrous. Her sewing basket, for example, featured iron-on patches and some random buttons. Thrift might have appealed to her pragmatism; after all, she had lived through both the Depression and wartime rationing. But the ‘50s and ‘60s were about prosperity. People bought all those new appliances and gadgets, discarding the old.

Having come of age in the rock’ n’ roll, back -to-the-earth ‘70s, I had a different relationship to repair. A box of my jeans still survives from that long ago time, covered with elaborate patches and embroidered trim. They represent something more than thrift, memorializing dual impulses to make something beautiful and keep it alive-- eke another month or year of wear from a beloved garment. I still patch the knees of work pants, unwilling to give in and discard. Too many things get thrown away. I no longer embroider or elaborate, but I try to make the repair aesthetically, unable to stop myself from caring.

What is mending, anyway? The dictionary describes it as taking something that is damaged and making it whole or useful once again, free from faults or defects. It can also have a moral tone—mending your ways— and even refer to the return of health, when you are on the mend. Mending fences describes the act of making peace. The word implies something restorative and positive, whether gentle or radical. Mending is a kind of added value: an intervention, ranging from the invisible to all but replacing the matrix that serves as its host.

Over the next year, I’ll be writing here about contemporary artists for whom mending plays a significant role in their practice, providing some part of the impetus for work in a wide variety of media—not only textiles and ceramics, but metal, wood, photographs, painting, and even the world around us. Their motivations might be environmental, ethical, or purely formal. Some makers are practical bricoleurs; some are experimenters, some are healers. Some draw on traditional methods and practices, while others invent something astonishingly new.

There will be interviews, essays, and lots of pictures. If you know of a Mender, please drop me an email to tell me about her or him.

Here is a brief preview of some of the artists I am presently thinking about:

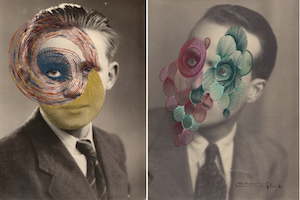

Maurizio Anzeri embroiders found photographs. Many are of people; others feature landscapes. The parallel threads transform the images in surprising and haunting ways.

Ramekon O’Arwisters cradles ceramic shards with crocheted textiles. He also works with groups of people, teaching them to crochet fabric in a kind of collaborative craft therapy.

Jim Bachor builds pothole installations: exquisite mosaic still lifes and portraits that beautify the urban environments in which he executes them.

Debra Broz reinvents ceramic figurines by joining together disparate parts into brand-new wholes whose seamless perfection defies what we know as reality. Most are very funny as well.

Bouke De Vries often uses fragments of antique ceramics, drawing on his experience as a restorer to make viewers think about what value remains after something is broken.

For De Vries, mending is as much destruction as it is repair.

Bridget Harvey investigates process through making. She “playfully examines the 'optional durability' of our possessions with a focus on repair,” working with textiles and ceramics and… whatever seems interesting and appropriate.

Jaydan Moore deconstructs and reassembles found silverplate tableware into previously unimagined configurations.

Hannah Streefkerk mends landscapes, on an improbable scale. She describes her work as restorations, sometimes of delicate materials like bark, that address the passage of time. She has mended fields, forests, and even a quarry (above, left).

Helen O’Leary joins fragments of wood in abstract compositions that look as though they are lighter than air. She describes these pieces as part of a narrative that describes “greatness fallen on hard times.” She cuts apart the stretchers and panels of earlier paintings, gluing and patching them together: working the studio as her father worked the family farm in rural Ireland.

And Jan Voormann fills in holes in brick walls with plastic construction blocks. (Think Legos.)

There is always more mending to be done. Stay tuned.