Some thoughts about cloning, twins, and Alice Shaw

Dearest friend:

The first fraternal twins I ever knew were Alice Shaw’s youngest siblings. It would be more appropriate to call them sororal, as in sisters, utterly unlike each other, as two children born from two different eggs would logically be. Like most people, I hadn’t really thought about this fact—that twins can be nonidentical, even as they are truly twins—but Alice has lived most of her life with such knowledge, having been seventeen when they were born. And while it isn’t the only reason she has long been interested in a constellation of ideas around twinning/ reflection of the self, I cannot help but think that it has been instrumental in the development of several bodies of her conceptually-driven work.

People Who Look Like Me (2006), a book project published by Gallery 16, features Shaw paired with someone/thing with whom/which she has some kind of visual commonality, however obscure it seems at times. A gap between front teeth revealed by an engaging grin; similar glasses, lipstick or clothes. In one memorable image, both figures wear the same hideous athletic shirt. After a while you figure out that, like Cindy Sherman, Shaw is experimenting with being a chameleon, finding and revealing secret shadow selves, even when the Other is a horrific wig-styling toy or an exotic tiger-striped Bengal cat. These are all portraits of non-identical twins, akin to Shaw’s little sisters.

Even more striking in this ‘unmatched’ genre is her body of work collectively titled Opposites (2007). For these, Shaw sought a physical counterpart to her own attributes as “a small white middle-aged woman who often feels that I have more male traits than female traits.”

This reverse-doppelgänger turns out to be a tall teenaged transsexual African American. In ten diptychs, Shaw and her Other strike similar poses, in similar states of dress/undress, in various rooms of a high-ceilinged Victorian house. I’ve never seen anything like these pictures. Their strangeness is enduring, and affects me as much now as it did when I first encountered them, over a decade ago.

In 2009, Shaw devoted an entire show to what she called (auto)biography. It included examples of handwriting analysis; of getting her palm and psyche read; of 'her' color (hot pink!), and even a rubbing of a tombstone engraved with her name. Though not strictly a consideration of pairs, these peculiar self-portraits suggested an alternate form of (un)duplication. The only actual pictures of Shaw that were in the show seem to suggest the extent to which a photograph can be manipulated to portray a fictional self. The first looks like a paparazzi candid-- Shaw as a giddy party girl in a preposterous hot pink lace-and-satin dress, nails and lips painted, a champagne flute in her hand and eyes closed in giggling rapture. The other is a haunting, silvery daguerrotype of the artist as an ghostly turbaned houri. Alter egos, separated at birth?

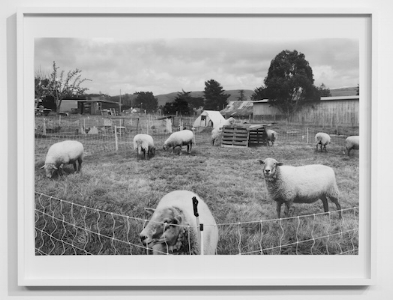

It’s Shaw’s most recent meditation on twinning that I am thinking about this morning, however. In her recent show at Gallery 16, titled Clones (2018), described as “an exploration of dichotomy and duplication,” she has turned her camera on—sheep. Various pictures of these animals, photographed in black and white as well as in color, feature them in positive and negative versions (Ba Ba Black Sheep);

facing in opposite directions; in stereo (in a fantastic homemade stereo viewer); in a series called—groan-- Lambscapes-- and even in a lenticular image titled Two Sheep in which only one of the two animals can be seen at a time.

Sheep/3:03:38-3:27:44pm shows what appears to be many sheep in a wire pen, but, as the title reveals, is a multiple exposure in which only a single specimen was involved-- as is the case throughout the show. Casper, as he is called, belongs to one of Shaw’s friends.

There are only two exceptions to this sly starring role (so like Shaw’s own self-portraiture in its utter quirkiness). In one, a video Shaw took features Dolly, the world’s most famous cloned sheep, beautifully taxidermied and posed on a revolving pedestal at the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh.[1]

The other Casper-less work is Pair, the large carbon print photomural at the show’s entrance, of two lambs on a hillside. (you can see this image at the top of this text.) It was made from an old glass slide Shaw found on Ebay. (She originally conceived of it as providing atmosphere, rather than being part of the exhibition.)

The joke here, of course, is that most of us can’t tell one sheep (a word that is the same in its singular and plural form) from another. In fact, many viewers didn’t actually realize that the subject in all of these pictures is the same, single sheep. This elaborate conceit is a reminder of the thing that photography can do that other media can’t: make infinite numbers of all but identical replicas. Yet even though Shaw ‘clones’ Casper-- making pictures in multiple ways, old and new, traditional and artisanal --it’s almost as if she is asserting that he’s different, even if only in the tiniest and most subtle ways, from one moment to the next, aging imperceptibly, changing through experience and knowledge.

And, anyway: which picture is the original here, and which the duplicate? In an age of mechanical reproduction, which is the work of art and which is the barnyard animal? The mind reels.

100 Sheep, an artist’s book published by the gallery in conjunction with Clones, is essentially a flipbook of 100 images, shifting from a field of white, out of which Casper gradually emerges, to a rectangle of black. Flipping the pages brings to mind counting sheep as an aid to sleep, slipping (hopefully) into oblivion. It also serves as a melancholy reminder of the transient nature of all images. Everything, Shaw’s sheepish portrait seems to say, passes as quickly, lost in a torrent of news/ social media posts/ ads, ad nauseam.

I’ve written about Shaw’s work more than once—partly because I admire it and her, and partly because we have known each other since the mid ‘80s, when we both lived in a warehouse in East Oakland. I was a feckless young artist; she was attending SFAI, her sisters just toddlers. Time passed and we both moved on, and eventually I had my own non-identical sororal twins, giving a greater depth to my understanding of Shaw’s experiences and insights and maybe even enhancing my considerable pleasure in her originality and humor. But you don’t need to be a mother of twins to get it. As I once wrote, her work is a reminder of photography’s promise: that being able to see what we look like on the outside will somehow confer new knowledge of what lies within.

Time for me to end this. One last thing-- the next time you leave from San Francisco Airport for an international destination, don’t miss Shaw’s public art work in Departure Area A. Ironically (considering its location), it is the antithesis of transience: a photomural measuring 20 by 26 feet of a hillside of majestic redwoods, the interstitial sky between trunks and branches covered with gold leaf like a Byzantine icon. Here’s a preview for you.

Have a great trip, wherever you are headed next. And don’t forget—you take your mental landscape (and yourself, your Other) with you, wherever you go.

Yours in sororal solidarity,

Maria

PS-- It was no accident that the invention of photography and the inception of psychology happened simultaneously. They have always paralleled one another, and I feel there still remains much in common between the two disciplines. They introduced two new languages. They were two new structures to read how we see things. -Alice Shaw

PPS- To buy the book version of 'People Who Look Like Me' or '100 Sheep,' contact Gallery 16.

******************************

[1] http://dolly.roslin.ed.ac.uk/facts/the-life-of-dolly/index.html