Mending money: Lisa Kokin

I.

My work often involves paradox. An aesthetically appealing image, when observed from afar, does not reveal the thought-provoking content which becomes apparent when viewed at closer range. -Lisa Kokin, artist’s statement

Thread is the place where the textile subtext of our lives begins and ends, and the slender connection to everything between. As a material, thread winds its way so far back in time that it is impossible to determine or even imagine who might have first made it, patiently twisting together plant or animal fibers. Its starring role in myths and fairytales has made it a metaphor for everything from love to greed, continuity to endurance. Thread connects, corrects, mends and embellishes. It has even entered the world of the internet, as a term for chained remarks on a topic in an online discussion.

For Lisa Kokin, thread has always been both idea and material. Her immigrant parents were upholsterers by trade; her grandma worked in a tie factory. Kokin got her first sewing machine at nine, and soon began making her own clothes. As an artist, her work has included a substantial range of methods and materials, but thread itself has connected most of the parts of her career: used to stitch together disassembled books, old photographs, buttons, zippers; to create both words and images and- most recently—to transform thousands of shreds and tiny cut fragments of paper money into works of art.

Still, as much as Kokin finds sewing to be almost as familiar as walking or breathing, it serves as a means and not an end. For decades, her practice has been conceptually-driven, as familiar, every-day materials are used to address subjects which she has described wryly as “hard to talk about.” It is all but impossible, she has discovered, for people to agree about the rightness or wrongness of certain actions. What is clearly inevitable and necessary to some is just as obviously ignorant and superfluous in the eyes of others, particularly in the context of religion and government. Sometimes, she asserts, the only way to come at an issue is indirectly; to show and not tell. Subjects she has made work about range from the deeply personal to the broadly political. They include, among other things, the impossible panaceas offered by self-help books; her own complicated relationship to Jewishness and Israel; guns and violence, environmental degradation, Karl Marx’s Das Kapital and the evisceration of the Voting Rights Act.

Since the 2016 presidential campaign began, she has been preoccupied with the grotesquely outsized role that money has come to play in elections, controlling outcomes as it flattens all dissent in its path, destroying institutions and people. She sees her current work as a way to process her grief for the death of democracy.

Mourning is something with which Kokin is deeply familiar. After her mother’s death in 2011, she spent some nine months making a body of work that was both about and for her deceased parent. “When there’s a death, you need to close the hole that’s left by the loss … it was a kind of psychological mending. Though I wouldn’t have used that word. We had a good relationship, so there was nothing to fix. And she had had dementia for many years before. She was almost 100, but it was still a loss. The work helped me to get the closure I needed.”

In art as well as life, thread’s role depends on how it is employed. Woven, it becomes a surface, goods, stuff-- a thing. In contrast, when used to sew, thread usually serves as a means, connecting or decorating other materials. For Kokin, thread has come to occupy a magical place between these two, successfully functioning as both through an ingenious combination of method and material. Using her machine, she sews intricate images (and often text) onto a water-soluble matrix—a translucent polyvinyl alcohol film[1]. When the completed piece is washed, the film dissolves. Only the thread remains, becoming, like a spider’s net, a miraculous thing that is both delicate and surprisingly strong.

Just before she passed away, it seemed as though Kokin’s mother knew that the end was imminent—or had, in some sense, become ready for it. During a visit two days before her death, Kokin remembers her saying emphatically, over and over, “Take me home NOW.”

In the months that followed, Kokin sewed these last words over and over, as they became the basis of several pieces. In two horizontally-oriented rectangles, the word now is most clearly readable. The stitched script, chains of thread and words, evokes both stria and strata—scratched marks on the surface of rock, as well as successive layers, accumulated over time. The horizontal rectangle suggests an open book, its pages completely covered with scribbled words.

This idea of marks serving as a kind of record-making or -keeping is evoked even more strongly in the circular pieces that came next. Including the word record in their titles, Kokin created a double meaning (as she often does), referring not only to the notation of speech that these represent, but additionally to the resemblance of these pieces to vinyl LPs. In one, the words take me home now are stitched in a spiral, like the grooves into which a needle enters to play a record’s sound. At the same time, the densely sewn text looks a bit like tree rings, while the pieces’ overall form makes us think of clocks, sundials, and countless other measuring devices.

Prayers in Hebrew appeared in two haunting works titled Ninety-nine Leaves #1 and #2. These cascading veils of pale leaf ‘skeletons’ incorporate delicate shreds of printed text taken from the remains of a prayer book Kokin found at a salvage yard.

In both of these pieces, there is one leaf for each of her mother’s years. Kokin found and pressed the actual leaves that served as her patterns in the course of a walk she took a few hours after her mother had died. These familiar shapes—maple, oak, eucalyptus-- function both as apt symbols of the transience of life itself and as a reminder of its cycling return.

_______________

II.

No one values money in this impotent state. It no longer has the ability to poison relationships, threaten democracy, topple governments, create privilege and misery. Stitched together with metallic thread into textile fragments or wrapped around wire and made into crowns, the material is re-contextualized with a new value and purpose. --Lisa Kokin

Since we began to think of ourselves as modern, artists have been experimenting with unusual materials—sometimes out of necessity, when little else is available, but just as often as a deliberate choice. Sometimes a medium conveys its own set of pre-existing meanings before the maker even begins, creating a mission or expressing an attitude merely by being itself.

Take money, for example. A surprising number of people have chosen to manipulate currency, whether by stamping single bills with text (Rirkrit Tiravanija) or painting out all but a few select details (Hanna van Goeler), the latter approach drawing attention to what remains in a rectangular field of white gouache. Mark Wagner destroys thousands in paper bills every year, cutting them into fragments to construct elaborate and mostly figurative collages. Justine Smith shapes the money into guns, tools, and delicate flowers. Ray Beldner sews it into replicas of famous works of art[2].

Though these works are all different, they have a crucial element in common. They make us think about money’s symbolic nature—both in terms of its value and, in some cases, the imagery used on it. The exchange of paper currency is a supreme act of faith, since it is no longer backed by reserves of silver or gold, as it once was. When governments need more money, they simply print it, though this can have-- unfortunate consequences[3].

For Kokin, the troubled relationship between money and power has remained compelling, though years have passed since she began to consider its implications and respond to it. In the months before November 2016’s presidential election, as the rhetoric about immigrants and walls and ‘fake news’ heated up, she funneled her increasing distress into making pieces out of currency. She called the body of work Lucre—a word that rarely appears without its modifier ‘filthy,’ due in part to the fact that it refers to money obtained dishonestly. In the ‘90s, Kokin had experimented with a bag of shredded bills before moving on to other materials. Decades later, a combination of disbelief and despair compelled her to take this material up again. “You can’t help seeing every day the destructive role that money and profits are having in the world. Money comes before anything and everything,” she told me. And it does. Our current crisis (as I write this, Covid19 has spread throughout the world) has made the gap wider and more dangerous than ever: the gap, that is, between the one percent holding most of the nation’s wealth and everyone else.

Though deconstructed bills are available from a variety of sources—Etsy, ebay, Amazon—Kokin buys hers five pounds at a time from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. “The thing that I love about it,” she said, showing me a bag with an official seal, “is its fragmented nature. I sort the bits of money into different categories, by color and shape.

“The titles of the pieces are a hint, but I don’t go out of my way to make it obvious that it’s money. People have to really look to see what the work is made out of. It’d even be fine if they don’t get it.”

When she says things like this, I sometimes wonder if Kokin is making a private joke. Her sense of humor, evident in the aforementioned titles, exploits various kinds of plays on words or historical references, all of which help to lay a trail of breadcrumbs regarding possible interpretations. Sometimes meanings are hilariously (if painfully) obvious. Profit and Loss is a giant zero, painstakingly assembled out of a diagonal grid of metallic thread sewn through delicate shreds of bills.

Cold Comforter is a life-sized (five feet by three feet) rectangle of- holes. There is really no other way to describe the delicate network of mostly gray, irregular cells: empty centers with edges constructed out of bill shreds bound in silvery thread. As Renny Pritikin wrote in a 2018 essay about Kokin, “A blanket full of holes is cold comfort, as is a compromised social safety net[4].”

Other pieces refer directly to Trump’s favorite project, the much-vaunted wall. (De)portable is constructed out of dense-looking ‘bricks’ of textured green papier mache—one of few of Kokin’s ‘money’ works that is not sewn. Beyond the Pale is an exquisite double grid, squares and diamonds, made of thread and shreds of bills: a severely elegant geometric abstraction that suddenly, shockingly, reveals its resemblance to a chain link fence. For Jews, the expression ‘beyond the pale’ can be understood as referring to much more than acting outside the bounds of acceptable behavior. The Pale was the part of the Imperial Russian empire within which Jews were permitted to live between 1791 and 1917—an increasingly small area that, at one point, was home to 40% of the world’s Jewish population. Recurrent pogroms and increasingly restrictive decrees led to massive emigration, much of it to the United States. After WW1, most of the Pale became the restored country of Poland. A generation later, all but a few of Jews who remained there died in the Holocaust.

Kokin’s family were a part of that story. Both of her parents were born in the US, but their families had come from Romania and Russia in the first decade of the 20th century, as millions of Jews fled poverty and persecution. Kokin remembers her family as politically active-- especially her mother, a member of the Workmen’s Circle and of the American Labor Party ( a breakaway group that separated from the Socialist Party in the late 1930s, supported largely by the needle trades unions and garment workers). The Workmens’ Circle was founded in 1905 as a mutual aid society, providing insurance, unemployment support and even burial assistance for Yiddish-speaking immigrants. Today, as the Worker’s Circle, the organization still promotes secular Yiddish culture and language studies as well as social and economic justice (and a summer camp that Kokin fondly remembers attending).

As a young adult, Kokin worked towards political change throughout the ‘70s and ‘80s. She was active in the Latin America solidarity movement against intervention in Chile after the coup in 1973, later focusing on El Salvador and Nicaragua. She funneled her artistic energy into figurative batiks about countries “trying to throw off the yoke of U.S. imperialism,” showing this work in Brazil, Nicaragua and Europe. “I was invited by the Sandinistas to have a solo show in 1983… I’d gone to Cuba with the Venceremos Brigade in 1979, building housing for textile workers.” At some point, however, her desire to mend the world politically through leftist imagery began to shift. “I wanted my art to influence people's opinions and help promote change. A not unreasonable thing for a young person to believe...but in retrospect somewhat naïve.”

After returning to school—she had interrupted her education for political activism—her convictions did not change, but her interest turned towards other materials and approaches. She realized that “there's a lot of grey between the black and the white. I no longer aim to convince, merely to show… I still feel that capitalism is an inhumane system and always will feel that. What the alternative is is not so clear to me. I don't hold up Cuba anymore as some kind of gold standard, because the suppression of dissent is problematic for me.”

__________________

III.

I like money in its shredded state because it is stripped of value and power. Worthless, it becomes just so much green and white confetti. It is literally not worth the paper it’s printed on. -LK

It is difficult to ignore the parallels between today’s anti-immigrant xenophobia and yesteryear’s religious/ cultural persecution. Or, for that matter, to view an increasing aggrandizement of executive branch power with anything but panic. The latter, and its unpleasant whiff of oligarchy bordering on neo-monarchy, has clearly been on Kokin’s mind. A protracted series of elaborate money-and-thread doilies, collectively titled Let them Eat Cake, serves as a reminder of where runaway uber-privilege has ended in the past[5].

Then there’s a group of towering crowns made from wire wrapped in bill shreds. Topped with ‘jewels’ thriftily made from a mass of multicolored thread ends, dog hair and dust collected from the studio floor, these imaginative examples of headgear are both ridiculous and sublime, one resembling nothing so much as a dunce cap.

Other works resemble fragments of ancient textile, or abstract Minimalist compositions, but the titles always offer clues. From the crazy quilts of tiny fragments in the Almighty series to the ‘log cabin’ pattern of Void; the hounds-tooth of Dog Eat Dog, to the elaborate repeating floral scrolls of Brokeade, Kokin is mending money as a way to talk about the breakdown of the social fabric.

Where do the bills come from, I wonder. She shrugs. A little digging online reveals that money is shredded under three circumstances: when it wears out, when it’s discovered to be a forgery, and when it’s misprinted. Some of the bill fragments in Kokin’s work are worn, while others appear to be brand new.[6]

Recently, Kokin has been experimenting with smaller and smaller fragments, gluing them on paper instead of sewing them, composing them into small rectangles the size and shape of cell phones. This current iteration suggests both the currency of virtual communication—increasingly important, in the era of Covid19—and the Big Brother-ish omnipresence of the internet. She confesses to being forced to leave her phone in another room at times in order to concentrate, a strategy with which I am familiar. One group of pieces takes tiny shreds of color to create meditative mazes; another builds dense vertical stripes that suggest the warp of a loom. Yet another pictures tiny KKK hoods.

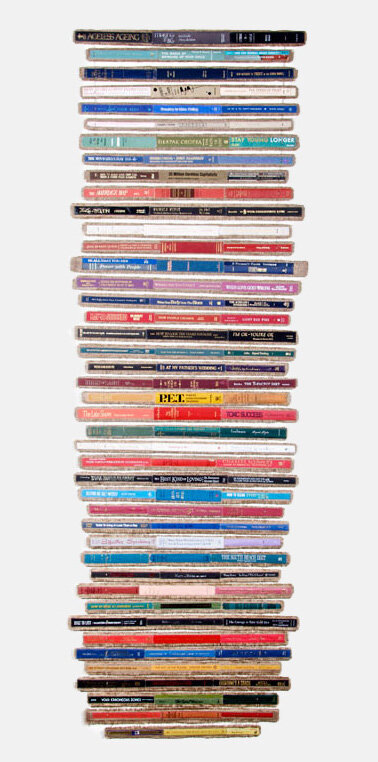

Viewing her enterprising use of every last bit of currency, I wonder if her thrift is something she was raised with, like progressive politics or her prodigious sewing skills. She reminds me that her parents, having grown up during the Depression, believed that wasting anything was immoral. For her, though, it’s more a matter of challenging herself to use everything-- of making art out of materials that no one else could or would use. I am reminded of her series based on self-help books, in which she used the entirety of each volume—snout to tail, so to speak—in different works. The front covers, for instance, appear in How to Stop Worrying and Start Living, cut into stylized petals sewn into bulbous, determinedly cheerful flowers (“which I hope will create eternal happiness for the viewer in five days or less,” Kokin once wrote). Each of the irregular, rock-like shapes in Room For Improvement consists of the pulped pages of a single book, mashed and molded into a tiny boulder to be pushed, a la Sisyphus, up the steep slope of acutely-felt personal lack towards some unattainable goal. In Treatment, the book’s spines are sewn, row after row, into a free hanging, two-sided vertical form, not unlike a Venetian blind. (Here, too, Kokin ‘s title is a double play. Not only do all of these volumes purport to mend the problems they describe, but the blind that the piece’s form mimics is also known as a window treatment.)

I think about all the other materials Kokin has used over the years: old photographs, buttons, zippers, books, and various random patinaed junk. I wonder how many more money-based pieces she will make. She keeps having ideas, she tells me. And keeps feeling that it’s really important to bring these issues into the public eye.

“The government breaks the money, and I put it back together… in so many different ways,” she says, smiling. “The work itself is what keeps me sane.”

_________________________________

Footnotes

[1] https://www.sulky.com/catalog/sub/stabilizer/wash-away/solvy

[2] Notably, two different artists have literally made art out of honoraria, confronting viewers with money’s sheer physical presence. In 2011, German Conceptualist Hans-Peter Feldman turned the $100,000 Hugo Boss Prize into (used) dollar bills and covered the walls of a gallery at the Guggenheim Museum. More than twenty years earlier, Ann Hamilton took the $10,000 stipend she had received from San Francisco’s Capp Street Foundation and converted it into pennies, laying them in an overlapping carpet of gleaming brown copper that covered much of the space’s concrete floor.

[3] Printing more money, unless output also increases, can result in higher prices for available goods. https://www.economicshelp.org/blog/1377/economics/effect-of-printing-money-on-economy/

[4] Renny Pritikin, in “Lucre: Lisa Kokin,”Seager Gray Gallery, 2018, p. 15

[5] Attributed to Marie Antoinette, this phrase—supposedly uttered when she was told the peasants had no bread to eat—was more likely said by an earlier French queen. It has been used numerous times in recent years to describe an attitude of callousness towards and disregard for the working poor, or, during the government shutdown in 2019, towards federal workers struggling to survive without wages.

[6] According to the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, bills last varying periods of time before being taken out of circulation, from an average of 4.5 years, for a $10 bill, to 15 years ($100s). Though this figure may be changing due to the prevalence of credit and debit card transactions, bills are constantly being pulled and shredded. https://www.bostonfed.org/news-and-events/news/2019/07/when-bills-go-bad.aspx