Dioramas

An exhibition at Palais de Tokyo, Paris

Recreating a three-dimensional scene frozen in time and space, the diorama is usually

enclosed in a display case, composed of a painted backdrop, props and figures...

Although the etymology of diorama means “to see through”, the device also stands

as a screen onto which a world of fantasy and fiction merges with the display of

knowledge and science.— Text panel, Dioramas, Palais de Tokyo, 2017

The room is quiet and very dark-- like a theater before the curtain goes up, or a film begins. Standing there, I’m suddenly transported back to the moment at which my love of museums first began: of arranged, explained and exquisitely presented objects and images, housed in buildings that (more often than not) look like temples, because--well—they are, serving up the myths of history and culture.

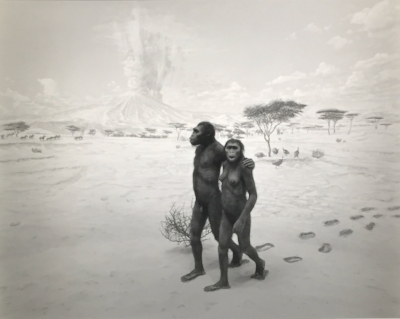

I try to remember what I was gazing at, entranced, at that long-ago primal instant. Was it a family of stuffed animals, posed in front of a painted sky? Or was it some Neanderthals, crouching in the dirt? I have stood in front of so many dioramas, lost in their worlds. Before movies-- let alone Virtual Reality Experiences—these magical windows invited viewers like me to project themselves into other times and places. Generations of museum-goers have enjoyed their effects, and the pleasant illusion that they offer some kind of real knowledge.

In Dioramas, curators Claire Garnier, Laurent Le Bon and Florence Ostende have assembled a spectacular and immersive exhibition exploring the history of this form and its influence on artists in the 20th and 21st centuries. The lightless entryway of this marvel-filled show is where my Proustian memory is stirred. The first thing visitors encounter, once eyes are accustomed to the penumbral gloom, is a loop from the 2006 movie Night at the Museum. Over and over, museum guard Ben Stiller spectacularly shatters the glass of the display purporting to tell the story of explorers Lewis and Clark, in order to free their beautiful native American guide Sacajawea. Serving as a kind of prologue, this film loop cleverly sets the stage for the rooms of dioramaphilia that follow, by defining and dissolving the ‘third wall’ at the same time that it suggests that there will be an examination/critique of the practices of museology.

In the first galleries, the story of the invention of the diorama as a theatrical venue in 1822 is revealed through Jean-Paul Favand's 21st century digital enhancements of Louis Daguerre and Charles Bouton's dreamy images, originally created on both sides of semi-transparent canvas. In the image shown here, plays of colored light illuminate the sun going down over the bay of Naples, while Vesuvius erupts nearby. These 'dioramas,' featuring current as well as historical events, became popular fairground attractions for the rest of the nineteenth century.

Continuing into the show, visitors soon discover that Catholicism was using some of the same display strategies much earlier, in works intended to stimulate faith during the Counter-Reformation. An assortment of religious events from the Bible or the lives of the saints are enacted by slightly creepy wax figurines in front of painted backgrounds. These are the first true dioramas, as the term is presently used; they were likely made by nuns in convent workshops, as a way of making visible the mysteries of faith.

In the next gallery, there is something quite different: displays of 19th-century taxidermied animals and birds, some in dramatic engagements (predator and prey, for example) in naturalistic settings. Some practitioners, though, went against this 'realistic' trend, seeking their inspiration in fairy tales or Christian themes. The fictitious 'happy family' pictured here of birds, rabbits, squirrels, mice, a monkey-- and even a cat-- is by celebrated English taxidermist Walter Potter. His own museum included some 10,000 specimens, presented in whimsical scenes like a schoolroom filled with fifty little rabbits in tiny suits of clothes, seated at desks.

In the hot, close dark (the day I visit, it’s over 90 outside, and considerably warmer within the exhibition) the next gallery presents one of the most important uses of display as educational tool. This is in museums of ethnography and history, where they became a vehicle for the preservation of the practices, dress and devices of the past.

The father of this kind of diorama in France, Georges Henri Riviere, is highlighted here for his innovative approach to conserving his nation’s patrimony. Some of the other ethnographic scenes feature excruciating moments of colonialism.

Like a kind of interesting punctuation, works by contemporary artists are interpolated between historical objects as the show progresses. Hiroshi Sugimoto’s photographs of natural history exhibits appear in several places, including not far from a

grid of transparencies of paintings used as diorama backdrops-- jungles, forests, rocks and clouds. Another contemporary work near these glowing rectangles is Jeff Wall’s Giant (1992), featuring an immense, naked, sixty-something woman, standing calmly in the middle of a library-- seemingly unnoticed by the patrons. The modest scale of this piece (19 x 23 inches), especially in comparison with most of Wall’s epically-sized work, invites close-up examination. The closer one gets, the more powerfully claustrophobic and disturbing it seems.

Sugimoto is not alone in his photographic examination of natural history dioramas. This subject has also been the subject of works by Diane Fox (represented here as well) and by Richard Barnes, who is known for his handsome pictures of all kinds of ‘behind the scenes’ moments at museums. Barnes' image of a man immersed in the task of vacuuming a bison display encapsulates much of what Dioramas is about, as evidenced by the exhibition’s curators’ description of the show as exploring the concept of the uncanny, describing it as ‘the unsettling experience of an everyday situation.’

The presence of photographs by Sugimoto and Barnes seems only right; there could hardly be a show about dioramas that did not include them-- or, say, Mark Dion, who has a piece in the large gallery at the end. There are, however, some surprises. These include Robert Gober’s weirdly intimate black and white photographs of-- natural history museum displays. At first baffling, these small images suddenly make a kind of sense when seen as studies for the artist’s truncated wax figures. Research reveals that, in fact, Gober has described his wax work as being “inspired by animal dioramas in a natural-history museum—examples of figurative sculpture far removed from the Classical tradition.”[1]. (Perhaps one of the catalogue essays explores this connection more thoroughly, but as I unfortunately can’t read French, I must rely on my own intuition and the few wall texts that have been translated into occasionally fractious English.)

Also revelatory are an enchanting series of pieces by Anselm Kiefer. They consist of two rows of boxes inset in the wall; these are filled with delicately layered silhouettes, evoking the worlds of fairytales and dreams. The artist describes them as “the story of a life in Germany at different stages: the peasant woman from the Black Forest with her great-grandson… the altar boy who wants to become a pope; a photograph drawn from a father’s war diary… or the walk with my friend during which Martin Heidegger’s brain suddenly lies on the soil of the forest...”

Other highlights include work by French artists Charles Matton and Richard Bacquie. There are several of Matton’s exquisite miniature rooms-- their contents scrupulously researched-- including Alberto Giacometti’s studio. In a minuscule version of a grand movie theater, a film plays on the screen. Bacquie, an iconoclastic and gifted sculptor whose career was tragically cut short at 42 by cancer, deserves much wider recognition than he has had outside France. His work here is a full-sized replica of Duchamp’s Etante Donne that breaks its illusions by removing the walls and its single point of view, allowing viewers to walk around the figure. For me, this disconcerting deconstruction of Duchamp’s masterpiece recalls nothing

else so much as the moment at the end of the movie The Wizard of Oz, when the charlatan of a wizard tries unsuccessfully to distract Dorothy and friends by bellowing “pay no attention to that man behind the curtain!” as he frantically manipulates his controls.

But I digress. As another one of the exhibition texts reminds us, “Staging a realm of optical illusion in which the laws of perception are constantly challenged, the diorama is a world of fantasy but also a critical platform for artists. What if the world we live in were nothing but a large diorama in which we experience the spectacle of our own life?” The curators drive this idea home by including a second film loop near the end of the exhibition. In this brief excerpt from the penultimate moments of

The Truman Show (1998), Jim Carrey/ Truman discovers that he has, in fact, lived his entire life inside a shooting stage by ramming his sailboat into the painted ‘sky.' Seeing a staircase in the wall, he climbs the steps. Carrey’s escape is a reminder that everything seen in the museum is framed by the building itself—by the fact of experiencing it here, bathed in the museum effect.[2] Each of these dioramas is a story within a story, and so on. There is no end.

As a final coda, a worker grasping a paint roller stands mutely by the exhibition’s door. This figure turns out to be a hyper-real sculpture by Duane Hanson from 1984-- symbolizing, perhaps, the end of make-believe (as the wall is returned to pristine white) and the return to reality-- as you walk out of the darkness, and back onto the streets of Paris, itself a giant open air museum. Turning to look back towards the river, the Eiffel Tower suddenly looms up in the near distance. Just for a moment, it looks painted, as if brushed on a backdrop of achingly bright blue. Then a family of tourists walks by, in terrible fanny packs and shorts, and everything is normal again.

__________________________________

[1] https://www.moma.org/collection/works/81069

[2]"The museum acquires social authority by controlling ways of seeing, and the objects around which museal vision is directed gather meaning from their context within the museum." http://www.archimuse.com/publishing/ichim03/095C.pdf

*************************************

Dioramas, which opened on June 14th, continues until the 10th of September, 2017. A substantial, heavily-illustrated catalogue with essays (in French) is available from Flammarion. The exhibition includes work by Marcelle Ackein, Carl Akeley, Sammy Baloji, Richard Baquié, Richard Barnes, Erich Böttcher, Jacques Bouisset, Cao Fei, Philippe Chancel, Joseph Cornell, Louis Daguerre, Giovanni D’Enrico, Caterina De Julianis, Mark Dion, Jean Paul Favand, Claude-André Férigoule, Joan Fontcuberta, Diane Fox, Emmanuel Frémiet, Ryan Gander, Isa Genzken, Arno Gisinger, Ignazio Lo Giudice, Robert Gober, Duane Hanson, Edward Hart, Patrick Jacobs, Arthur August Jansson, Anselm Kiefer, Fritz Laube, Pierre Leguillon, William Robinson Leigh, Charles Matton, Mathieu Mercier, Kent Monkman, Armand Morin, Lorenzo Mosca, Dulce Pinzón, Walter Potter, Georges Henri Rivière, G-M Salgé, Gerrit Schouten, Ronan-Jim Sévellec, Pierrick Sorin, Peter Spicer, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Fiona Tan, Jules Terrier, Tatiana Trouvé, Jeff Wall, Rowland Ward, and Tom Wesselmann. Obviously, I've just scratched the surface with this brief essay. If we're lucky, maybe an American museum will stage an exhibition of this scope and caliber at some point in the future. If we still have museums.